International Day of Forests: Conservation groups alarmed that BC is backsliding on Old-Growth Forest Policy Progress

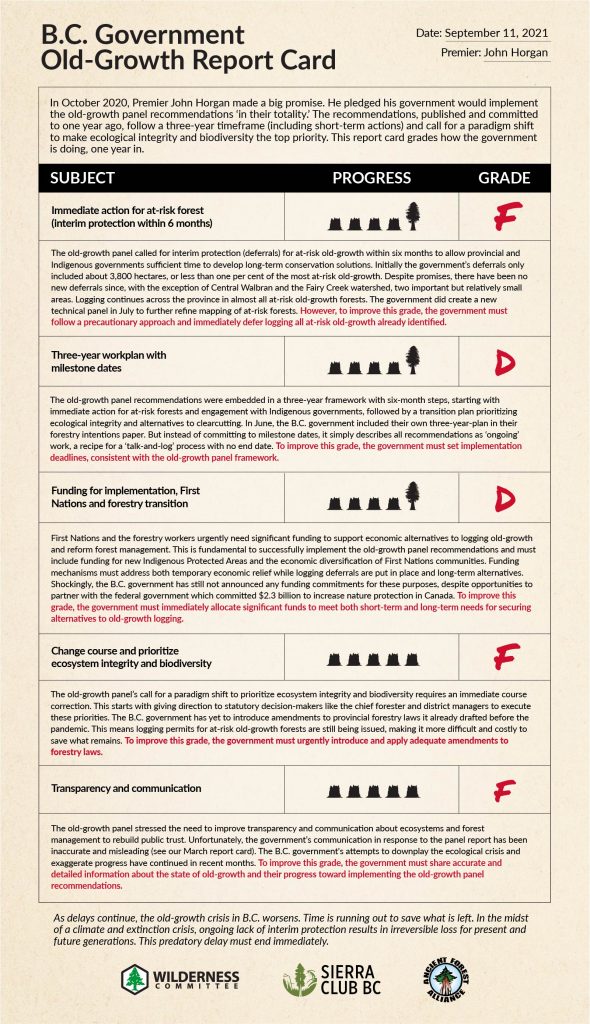

In light of International Day of Forests on March 21, the Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA) and Endangered Ecosystems Alliance (EEA) are expressing serious concerns that the British Columbian government is backsliding on its previous policy progress to ensure an ecological paradigm shift regarding its management of old-growth forests across BC.

“Despite significant conservation policy progress over the past year since Premier Eby came in, including his commitment to essentially double the protected areas system by 2030 and his allocation of major funding to enable this to happen, we’re concerned by what appears to be recent backsliding by the BC government on old-growth conservation,” stated Ken Wu, Endangered Ecosystems Alliance executive director.

“This includes all manner of sophistry by the Ministry of Forests to sustain the destructive status quo of old-growth liquidation, including having ‘deliberate bad aim’ to miss critical protection targets — that is, having an emphasis on saving smaller trees while the big trees continue to get logged; returning to the old dishonest ways of statistical PR-spin to mask their failures; promoting weak protection standards full of logging loopholes; facilitating the increased economic dependency of First Nations communities on old-growth logging; and doing a ‘slow walk’ in working with First Nations to implement old-growth logging deferrals in order to see the status quo further entrenched before any potential paradigm shift can occur.

“The forces of the old guard within government are working strategically to contain change and limit any paradigm shift to minimize the impacts of new conservation policies on the available timber supply — that is, enabling industry to ‘log until extinction.’ Eby is in charge, and he needs to do a selective harvest or controlled burn to cleanse the politics, policies and bureaucracy in BC of these old, unsustainable logging mindsets ASAP. I know he has the backbone for this, should he choose to do so. And we expect this now.”

Old-growth logging in Quatsino territory on northern Vancouver Island.

AFA and EEA acknowledge the genuine historic progress for old-growth protection that has been implemented under this BC government in recent times and are thankful for several significant leaps forward in conservation policy that Premier David Eby and Minister Nathan Cullen have implemented.

Positive steps toward increased old-growth protection:

- A commitment to incrementally protect 30% of BC by 2030 (currently, 15% of BC is in legislated protected areas).

- Securing over $1 billion to enable this expansion, which includes a dedicated $300-million conservation financing fund and a joint $100 million+ in a federal/provincial old-growth conservation fund.

- Floating a promising draft Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework (BEHF) that has the potential to direct protected areas establishment correctly via “ecosystem-based targets”, which would ensure that science-based targets span all ecosystems, including the most endangered and least represented ones.

- Establishing the Ministry of Water, Land, and Resource Stewardship (MWLRS) as a necessary coordinating agency in land and resource management.

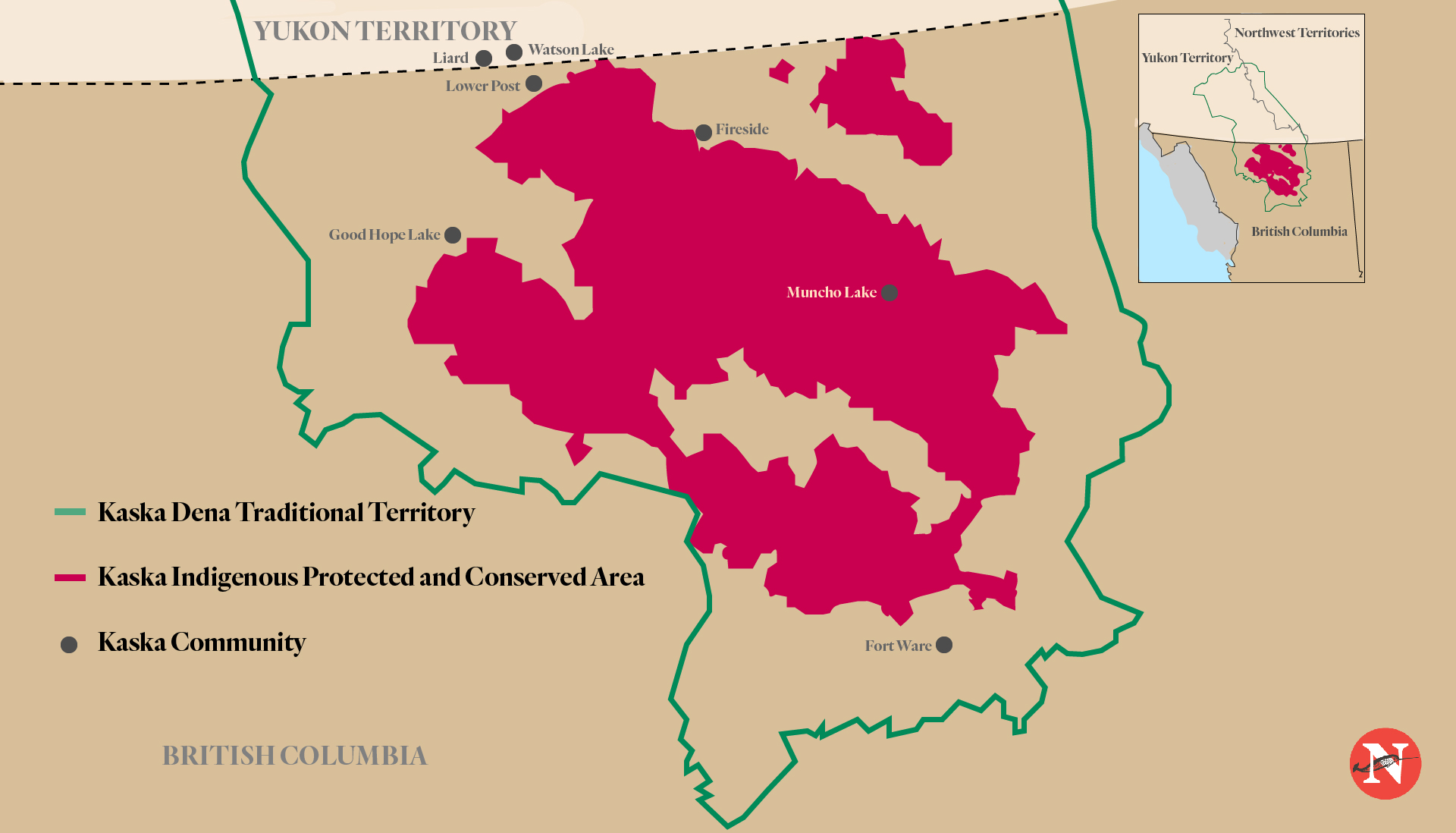

- Supporting several Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) plans, including the Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht conservancies recently announced in Clayoquot Sound and protecting the Incomappleux Valley last year.

However, key issues threaten this progress, including:

- The failure to secure old-growth logging deferrals for half of the priority most at-risk old-growth forests (the grandest, oldest, and rarest) as identified by the province’s appointed science team, the Technical Advisory Panel (TAP). After over two years, only 1.23 million of the 2.6 million hectares are secured. This is primarily due to the BC government’s unwillingness to provide deferral or “solutions space” funding to cover the lost revenues of First Nations who have an economic dependency on old-growth logging in their territories. This has been an ever-present failure of this government.

- The BC government’s refusal to proactively identify and add incorrectly categorized old-growth forests that, in truth, meet the criteria for priority deferrals but were missed in the initial TAP mapping exercise. Currently, the province is providing guidance to industry on how to subtract incorrectly identified at-risk old-growth forests from the TAP maps. This “subtract, don’t add” policy for incorrectly categorized old growth that should be deferred from logging demonstrates an egregious bias toward the timber industry and a conservation loophole that must be closed.

- The alarming way in which the province is using misleading statistics to cover its failure to secure logging deferrals in the most at-risk TAP priority old-growth stands by lumping together vast tracts of much smaller trees/less at-risk old growth secured through unrelated deferrals. While all old-growth logging deferrals are welcome and needed (the separate set of deferrals are forests that First Nations have identified as important for cultural values or are included in Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) proposals are important areas too), but not identical to the grandest, rarest or oldest stands identified by the TAP which must always remain a conservation priority), lumping the smaller trees together with the biggest and most at-risk old-growth categories to produce an aggregated number of 2.4 million hectares serves to sow public confusion and enables the BC government to shirk its responsibility to secure the full 2.6 million hectares of the most at-risk categories. In truth, 1.23 million hectares of the 2.6 million hectares of priority, most at-risk categories are currently deferred. In addition, the Ministry of Forests is also lumping together the TAP priority deferral areas with forests already protected in provincial parks and conservancies to get credit for “deferring” forests that had been protected for decades. These disingenuous and misleading statistics sow confusion and create mistrust. Fundamentally, these communication strategies suggest that the province is not prioritizing the full implementation of the 2.6 million hectares of TAP priority deferrals, and instead is trying to escape its commitment to preserve the most at-risk, big-tree forests by substituting protection for less threatened areas with smaller trees and lower timber values.

Other major problems with BC’s old-growth policies thus far include a lack of ecosystem-based protection targets to guide the protected areas expansion (which may yet come via the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework) as well as the weak protection standards of conservation reserves such as Old-Growth Management Areas, which has boundaries that can be moved around due to the influence of the timber industry lobby, and Wildlife Habitat Areas, which can be logged.

Additional issues include the province facilitating an increase in the economic dependency in many First Nations communities on old-growth logging, a lack of proactive advocacy by the province to foster new protected areas at planning tables and in general (rather, new protected areas are solely based on the will of First Nations, with the province doing nothing to actively identify and champion additional potential protected areas based on their high conservation values, subject to First Nations consent) and a lack of sufficient scale economic transition policies to move the timber industry away from old-growth toward second-growth stands.

“We’re in a global biodiversity and climate crisis, with the planet just experiencing its hottest year on record,” said TJ Watt, Ancient Forest Alliance campaigner and photographer. “Endangered old-growth forests in British Columbia, which store vast amounts of carbon and are havens for diverse species, are the antidote for what ails our world. On International Day of Forests, Premier David Eby and the BC government must renew their commitment to ensuring the old-growth forests identified as most at-risk are protected. At least $100 million in ‘solutions space’ funding that helps offset lost logging revenues for First Nations who are being asked to defer the most valuable and at-risk forests in their territories, along with the implementation of ecosystem-based targets that prioritize the protection of rare, big-tree old-growth forests and other highly endangered ecosystems, are a necessity. 1.3 million hectares (roughly half) of the old-growth forests identified by the old-growth science panel as being most at-risk remain undeferred and open to logging. Will Premier Eby oversee these endangered forests persist into the future or risk their permanent destruction? The BC government has a global responsibility to do the right thing.”

To turn this around, the province must:

- Truly commit to the mapping and the spirit of the TAP methodology, which prioritizes protecting the threatened big-tree old-growth forests. This means identifying barriers to protection and creating a credible, transparent strategy to overcoming those barriers, such as committing $120 million in “solutions space” funding to allow First Nations to accept these deferrals without facing financial hardship from lost logging revenues, as well as pursuing the continued addition of forests that were missed in the initial mapping exercise through ground-truthing and improved inventory data.

- Develop a rigorous and binding Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework that mandates fine-filter ecosystem-based protection targets incorporating forest productivity distinctions, for all ecosystems across BC. This framework must scale up protection by incorporating the latest conservation biology science and be developed by independent scientists and Traditional Ecological Knowledge holders, not representatives from industry.

- Close loopholes in current landscape reserves such as Old Growth Management Areas and Wildlife Habitat Areas to ensure they can’t be moved to facilitate logging or to allow logging within their boundaries. Until then, they must not be included in BC’s accounting of how much territory is protected as part of its 30% by 2030 goal.

- Create a BC Protected Areas Strategy informed by the forthcoming BEHF that identifies the priority areas for protection and that guides the expenditure of the BC Nature Agreement and Conservation Financing funds as BC expands its protected area system to achieve 30% protection by 2030.

- Ensure that the BC government is taking an active hand in regional planning, especially at the Forest Landscape Planning tables, by advocating for the protection of key old-growth ecosystems and making conservation financing funding available to enable First Nations to reasonably choose protection instead of timber extraction without major financial loss.

- Undertake a much greater economic transition policy of incentives and regulations to move the timber industry from an old-growth industry toward a modernized, value-added, sustainable second-growth industry, and to incentivize the development of a larger conservation-based green economy associated with an expanded protected areas system.

Without following these steps, BC will inevitably end up with a protected areas system that will continue to largely skirt around the rich valley bottoms and focus protection on predominantly alpine and subalpine areas with low timber values while the biggest trees continue to fall and BC’s 50-year “War in the Woods” will continue to flare up and rage on.

“The vast resources now available from the federal and provincial government for conservation must be laser-focused toward protecting the most biodiverse and threatened ecosystems, providing whatever resources First Nations need to offset lost revenues and allowing them to choose protection without taking significant financial losses,” stated Ian Thomas of the Ancient Forest Alliance.

“The forests that TAP recommended for deferral are endangered because they are also the most lucrative forests to log, and therefore, successive governments have largely avoided protecting them. That must change. Whenever the government uses misleading statistics to obscure the stubborn fact that 50% of the most threatened forests remain open for logging, they signal a wavering commitment to protecting the irreplaceable. The province, which has driven the liquidation of the oldest and most magnificent forests in BC for over a century, cannot just shrug its shoulders and walk away while the last of these threatened forests are destroyed. There are consequences for all with this approach — including for the government.”

“In short, the BC government is at a crossroads,” said Watt. “It can choose to bolster the significant strides it has taken toward protecting old-growth forests by closing the funding and policy gaps, helping to save endangered ecosystems while supporting conservation-based economies. Or, it can slink back to its old ways of fudging statistics to imply old-growth forests are not at risk while facilitating the destruction of the best of what little remains, leaving behind impoverished landscapes and communities.”

Wu said, “We have hope that Premier Eby will ensure that his old-growth policy progress doesn’t ultimately end up as a sinking ship due to the old-growth timber lobby and its friends. The forthcoming Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework, still under development, holds the greatest promise of all. The single largest game-changer in BC’s conservation policies will be if the BEHF mandates legally-binding, ecosystem-based targets that include forest productivity distinctions to ensure that the most at-risk, least represented ecosystems are protected based on science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Premier Eby must see this done.”

View these infographics that explain the central importance of “ecosystem-based targets” and a strong Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework here.

And see an explanation of why “forest productivity distinctions” must be included in ecosystem-based targets here.