May 28, 2024

By Shannon Waters

The Narwhal

Read the original article here.

With an election approaching this fall, the BC NDP government has released a surprise update touting ‘significant progress’ on protecting old-growth forests. We take a look at the reality on the ground.

It’s been four years since a pair of professional foresters hired by the BC NDP government urged the province to take a radically new approach to old-growth forests.

In their strategic review, Garry Merkel and Al Gorley said the government should manage BC’s old forests as ecosystems rather than a source of timber. They also called for an immediate deferral of logging in old-growth forests in BC at risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.

The report was released as protesters began to flock to Fairy Creek, a largely intact old-growth valley on southwest Vancouver Island, setting the stage for the largest civil disobedience action in Canadian history. Following the arrest of more than 1,100 people, and at the request of Pacheedaht First Nation, the BC government deferred just over 1,180 hectares of Fairy Creek old-growth forest from logging.

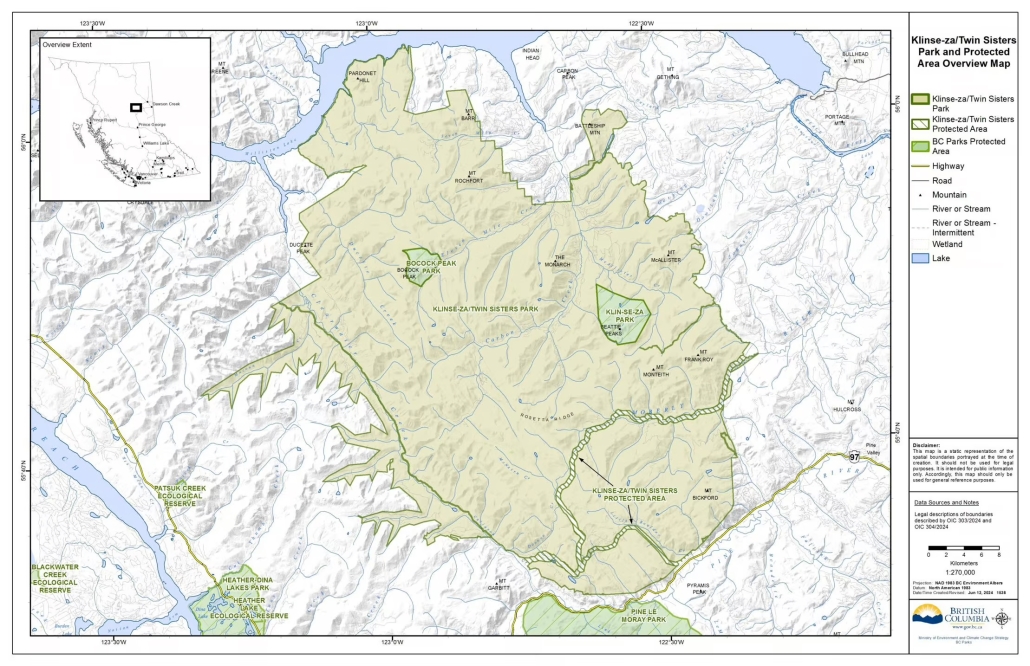

The Fairy Creek deferrals are included in more than 2.4 million hectares of old-growth forest “temporarily deferred from development” in collaboration with First Nations and industry, according to a May 21 old-growth “update” from the government.

The Fairy Creek blockade became the largest civil disobedience action in Canadian history. Logging was subsequently deferred in the old-growth valley on southwest Vancouver Island, in the territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The unexpected update comes as the BC NDP and other parties gear up for a fall election campaign. The latest poll shows the NDP only slightly ahead of the BC Conservatives, whose popularity has soared over the past year. If elected, the BC Conservatives are promising to “support BC forestry,” which the party describes as “sustainable and renewable.” They’re also pledging to hold groups and activists “who impede the activity of resource development through illegal blockades, harassment and violence” accountable, both legally and financially.

Against this backdrop, the old-growth update says the government has made “significant progress” on implementing 14 recommendations made in the foresters’ review of old-growth strategy. Yet it also cautions it “will take years to achieve the full intent of some of the recommendations.”

Environmental groups and the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs were quick to criticize the update, saying it lacks concrete commitments to urgently protect BC’s remaining old-growth forests.

“The BC NDP government has objectively taken us farther along than any previous government in bringing the key policy pieces together needed to protect old-growth and endangered ecosystems,” Ken Wu, executive director of the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, a national non-profit conservation group, told The Narwhal. But Wu said big policies like ecosystem-based protection targets are still missing, along with sufficient funding “to cover the lost forestry revenues of First Nations should they agree to implement old-growth logging deferrals.”

The Wilderness Committee, an environmental non-profit group, called the update a stall tactic that “delays meaningful changes and fails to include any new interim measures to protect the most endangered old-growth forests.”

“The endless delays from the BC NDP are resulting in the destruction of irreplaceable forests they vowed to protect,” Tobyn Neame, the Wilderness Committee’s forest campaigner, said in a press release. “Premier David Eby promised accelerated action on old growth, not another vague plan, and it looks like he is trying to tick a box without doing the actual work.”

But Merkel, who is working for the government on contract, urged patience, telling The Narwhal much of the work is taking place behind the scenes.

What progress has been made on implementing the old-growth recommendations? And what more needs to be done?

Read on.

Wait, why did the BC government commission an old-growth review in the first place?

The BC NDP’s promises to safeguard old-growth forests stretch back to before the party formed government. The party’s 2017 election platform promised to modernize land-use planning “to effectively and sustainably manage” BC’s old-growth forests. The campaign pledge followed several decades of a simmering war in the woods and an international spotlight on contested old-growth areas like Clayoquot Sound.

In July 2019, Merkel and Gorley were appointed by the province to “get input and hear perspectives on managing the province’s old-growth forests for ecological, economic and cultural values.”

How much old-growth forest is left in BC?

BC once boasted 25 million hectares of old forest but by 2021 only an estimated 11.1 million hectares of old growth remained, according to the province.

Ecologists disagreed with the government’s figures, saying less than three per cent of high productivity old-growth forests — the forests with the biggest trees and the richest biodiversity — were still standing. They found only 35,000 hectares of forest with the largest, most productive old-growth trees — areas where trees are expected to grow over 25 metres tall in 50 years — remained in BC.

The definition of old-growth forest varies depending on location. Coastal forests with trees at least 250-years-old are considered old growth, while interior forests with trees at least 140-years-old meet the definition.

What did the BC. old-growth forest review say?

Merkel and Gorley’s report called for a “paradigm shift” in the way BC manages old-growth forests, including abandoning the misconception they are a renewable resource.

“These ‘ancient forests’ are globally unique, rare and contain species as yet undiscovered, and many of these ecosystems and old forests are simply non-renewable within any reasonable time frame,” the foresters wrote. They said it can take 500 to 750 years before a coastal ancient forest returns after logging.

Logging trucks loaded with giant old-growth cedar trees are a common sight on Vancouver Island, including along the shores of Lake Cowichan. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

Old forests have intrinsic value for all living things, the report concluded, and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber. Merkel and Gorley recommended immediately deferring development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.” Prioritizing ecosystem health and resilience are among other recommendations.

The foresters also said the province needed to engage “the full involvement” of Indigenous leaders and organizations in an old-growth strategy.

Did the government follow the old-growth review’s recommendations?

Just ahead of former premier John Horgan’s snap election call in September 2020, the government announced 353,000 hectares of forest in nine areas would be protected under the strategy. Critics warned the move would not actually protect much old-growth forest.

During the 2020 election campaign, the BC NDP promised to protect “more of BC’s old-growth forests” by implementing all 14 recommendations in Merkel and Gorley’s old-growth report. But logging of old-growth forests continued, including in areas home to endangered caribou and spotted owls.

In November 2023, the environmental group Stand.earth estimated at least 31,800 hectares of forest recommended for deferral in 2021 had been destroyed.

According to the government’s May update, only two of the old-growth review’s 14 recommendations — “engage the full involvement of Indigenous leaders and organizations” and “defer development in old forests at high risk, until a new strategy is implemented” — have reached an advanced stage of implementation. Nearly half the recommendations are still in an “initial action” stage.

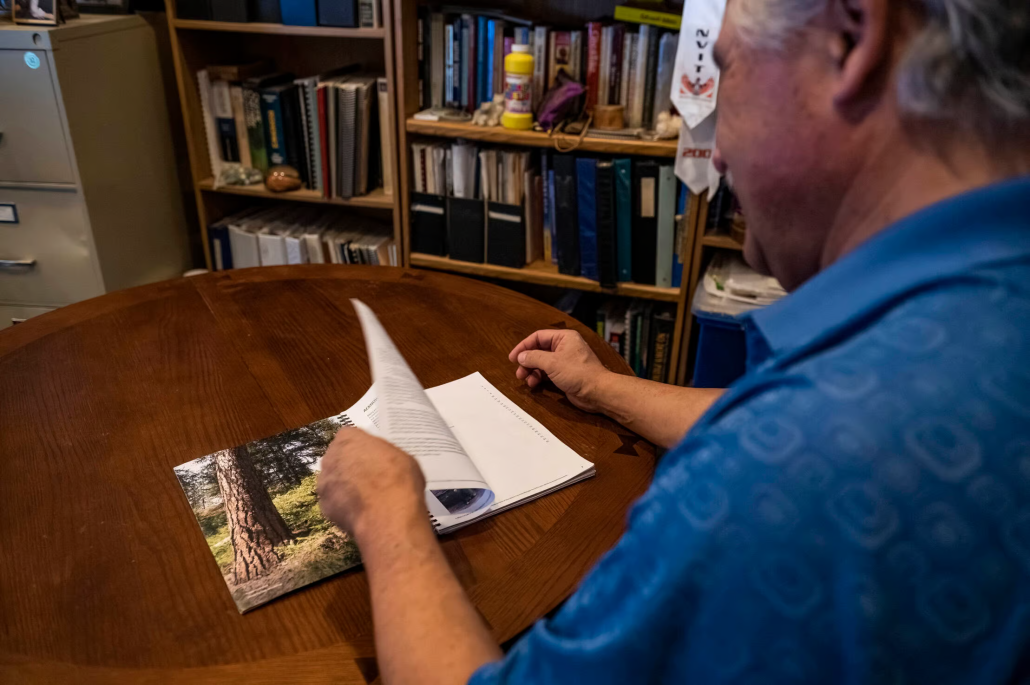

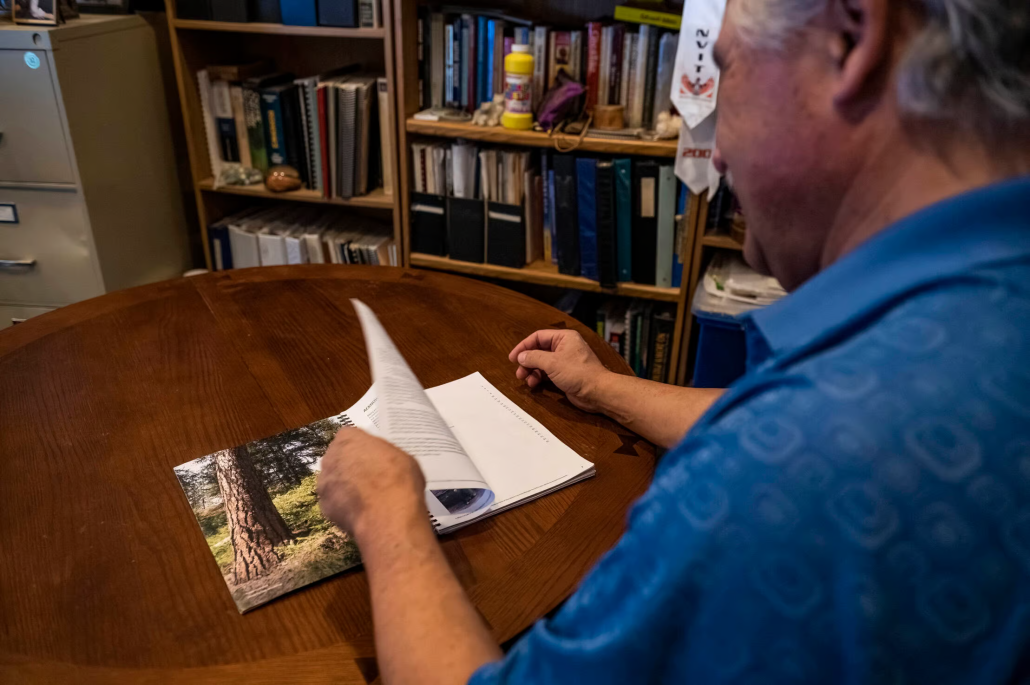

Garry Merkel, a member of the Tahltan First Nation, was one of two foresters commissioned by the BC government to examine the province’s approach to old-growth forests. The report the foresters submitted calls for a paradigm shift in the way BC manages old-growth forests, saying they should be managed for ecosystems and not for timber supply. Photo: Morgan Turner / The Narwhal

Following the old-growth update, the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs said the province needs to immediately implement all proposed logging deferrals, as well as additional areas proposed by First Nations and others that meet the definition of at-risk old-growth forests.

“We must take immediate steps to stop the logging of at-risk old growth on the ground,” union president Grand Chief Stewart Phillip said in a statement.

Why is BC taking so long to protect old-growth forests?

Wu compared the government’s efforts to protect BC’s old-growth — and its broader conservation policies — to a puzzle.

Over the past several years, several major policy pieces have been assembled that have the potential to effectively protect endangered ecosystems such as old-growth forests, he said in an interview. “Where my patience runs out, is where they’ve so far failed to put all those pieces in place.”

However, Merkel, now an independent contractor for the Ministry of Forests and the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, said the NDP government is about halfway toward implementing the old-growth panel’s recommendations, with much of the work happening out of the public eye.

He knows the seemingly slow pace has frustrated some observers.

“I tell people that we have to certainly be patient, but I don’t tell people to stop advocating and pushing,” Merkel told The Narwhal. “This is the kind of thing that if you don’t keep pushing, it’s so big that it just kind of gets lost in the background. … It’s very rare that government does something at this scale.”

How does reconciliation fit into BC’s old-growth forest strategy?

Merkel said implementing the strategy’s recommendations is complicated, in part because of the BC NDP government’s commitment to reconciliation with First Nations. The old-growth strategy is one of the first policies to put the government’s commitment to implementing its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act to the test because, Merkel pointed out, it is “tied directly to Aboriginal Rights and Title.”

Forester Garry Merkel, a member of the Tahltan Nation, says the BC government is about halfway to fully implementing the recommendations from the old-growth forest strategic review he co-authored in 2020. Photo: Morgan Turner / The Narwhal

“In BC, protected areas require the consent and shared decision-making of the local First Nations whose territories they will be established in,” Wu said. “Therefore, protected areas establishment ultimately moves at the speed of the local First Nations whose territory it is.”

After BC’s old-growth forest strategy was released, the Ministry of Forests presented First Nations with potential areas within their territory where old-growth logging could be deferred while long-term stewardship plans are developed. Merkel said the ongoing process involves First Nations, industry representatives and multiple ministries, with their work marking the start of a seismic shift in how the province manages land.

“The old-growth strategy wasn’t so much about old growth as it was about fundamentally changing the way you look at land and changing our land stewardship approach,” Merkel said. “Learning how to think about land as an ecosystem, as opposed to forest has been hard; learning how to enter into effective co-governance relationships, especially when multiple First Nations are involved, in trying to set up frameworks to collaborate in real time and make sure that they’re accountable to the public — it’s been really hard.”

What does reconciliation look like on the ground?

Na̲nwak̲olas Council president Dallas Smith, whose organization represents six First Nations on northern Vancouver Island and the central South Coast, credits the BC NDP government for working more directly with individual First Nations than its predecessors. Previous governments typically “tried to do things from a provincial perspective” by seeking support primarily from high-level organizations like the First Nations Leadership Council, Smith said.

The government has also supported policies that enable First Nations to take the lead in deciding how conservation and resource development takes place on their territories, Smith told The Narwhal. While progress may seem “glacial,” initiatives are moving forward, especially in areas where First Nations take up government policies that mesh well with their own priorities, such as Indigenous protected areas, he said.

“We’ve all found our little wiggle room in there to pull some of these initiatives that government wants to achieve, connect them to initiatives we’re trying to achieve in our communities and make some of that progress,” he said. “You’re seeing more and more nations figure out how to do it for their territory.”

As with the potential old-growth deferrals, First Nations will play a pivotal role in helping the province achieve its conservation commitments.

“First Nations are in the driver’s seat,” Wu said. “When it comes to establishing protected areas directly in any given territory, the BC government should be expected to provide the vehicle that is the policy framework and the funding to ensure that First Nations can drive that vehicle to where we all need to go, which is the protection of endangered ecosystems.”

Kwiakah First Nation is one such success story. On May 24, the nation announced it had reached agreement with the province and forestry company Interfor to reduce logging in 7,866 hectares of the Great Bear Rainforest and focus on restoring the land to “its pre-industrial state” through regenerative forestry practices.

“By creating the M̓ac̓inuxʷ Special Forest Management Area, we are asserting our inherent responsibilities and creating an Indigenous-led conservation economy that will steward and heal our territory while allowing our people to thrive,” Kwiakah First Nation Chief Steven Dick said in a press release.

The Kwiakah Nation said the new conservation area is a first step toward “rebuilding knowledge systems that protect and restore forests to old-growth characteristics,” while creating new jobs in land stewardship.

Conservation finance programs launched in the Great Bear Rainforest to date are credited with creating more than 100 businesses and 1,000 permanent jobs in ventures ranging from ecotourism to a sustainable scallop fishery.

Under the new agreement, any timber harvesting revenue the Kwiakah Nation loses out on as a result of the new management area will be counteracted through the generation of carbon credits and regenerative forestry jobs, according to the Ministry of Forests.

Displacing revenues related to logging ancient forests is key to achieving effective ecosystem protections, according to Wu — and something he says the BC NDP government has, until recently, failed to implement.

“That’s a biggie because you’re not going to get all the best places under deferral unless First Nations have economic support to implement those,” Wu said.

Last October, the province announced a $300-million Indigenous conservation fund to protect old-growth forests. The fund will support conservation initiatives, including Indigenous stewardship and guardian programs.

Wu called the financing a “vital enabling condition” to create more protected areas in BC.

What about ecosystem and biodiversity protection?

The update on old-growth protection also reveals another BC NDP platform promise is delayed. The government promised to finalize a new biodiversity and ecosystem health framework this year. But the update says the framework won’t be complete until 2025.

Meanwhile, a new report from federal think-tank Policy Horizons Canada ranks biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse second on a list of 30 potential disruptions Canada faces, in terms of likelihood and impact.

The collapse of ecosystems “could have cascading impacts on all living things, putting basic human needs such as clean air, water and food in jeopardy,” the report states. “Key industries like farming, fishing and logging could be hard hit, leading to major economic losses and instability.”

BC’s old growth forests are unique, rare and non-renewable, according to two foresters who were commissioned to write an old-growth strategic review for the provincial government. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Last November, the government published a draft biodiversity and ecosystem health framework that aims “to prioritize the conservation and management of ecosystem health and biodiversity, including the conservation and recovery of species at risk.” Public consultation on the framework closed at the end of January.

The framework will be backed by legislation, according to the update, and include guidance and standards for managing ecosystem health and biodiversity developed in collaboration with First Nations.

Wu called the framework “the last big piece” in BC’s conservation policy puzzle.

“The biodiversity and ecosystem health framework is the vital game changer that essentially can finish the puzzle,” he said.

In its press release on the old-growth update, the non-profit environmental group Sierra Club BC noted the framework is expected to include interim conservation targets to protect at-risk ecosystems without delay.

“What’s needed now is leadership at every level of government and in every ministry to protect irreplaceable old-growth forests before we lose any more,” Sierra Club BC campaigns director Shelly Luce said in a press release. “Meaningful action plans would move us beyond talking, to deliver on existing commitments and create change on the ground.”

Wu hopes the framework will lay out specific conservation targets for all of BC’s ecosystems, based on scientific and First Nations knowledge.

“Ecosystem-based targets are so foundational that, without them, it’s like … a surgeon who just has a target in kilograms of what they’re going to remove,” he said.

The old-growth update, however, makes no mention of ecosystem-based targets, worrying Wu.

Even if the framework delivers specific targets, he notes provincial cash will be required to help implement them.

Are there any other old-growth conservation efforts?

One thing the NDP government has definitely done right, according to Wu and others, is to commit considerable cash to conservation efforts.

Last November, Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen announced $1 billion in federal-provincial funding as part of an agreement with the federal government and the First Nations Leadership Council. The agreement includes commitments to support Indigenous-led conservation initiatives and restore 140,000 hectares of degraded habitat within the next two years. Part of the federal investment — $50 million — will go towards identifying and conserving up to 1.3 million hectares of old-growth forests.

Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen says there is “much done, more to do” when it comes to protecting BC’s at-risk ecosystems like old-growth forests. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

In December, the province also committed to protecting 30 per cent of the province’s land base by 2030, partly by creating new Indigenous protected areas, according to Cullen’s current mandate letter.

“The NDP have taken us further, so far, than any other previous government in history in moving forward with the enabling conditions and the policies that will lead to the greatest expansion of protected areas, including old growth, in BC history,” Wu said.

The province is currently hosting discussions about land management that include First Nations, local communities and governments, and industry representatives. There are nine land-use planning tables across BC that Cullen said are “well on their way and making new land-use plans in their region” — with 10 more tables still to be created. Their goal is to decide how to prioritize local and regional ecosystem health and biodiversity and determine how economic activities — from logging and mining to farming and fishing — fit within those priorities.

“Indigenous-led conservation through land-use planning processes is the way that we’ll achieve durable and diverse conservation,” Cullen told The Narwhal in an interview.

“That is where we’re able to find common ground. When you get down to the maps and valley by valley, interest by interest, you’re able to build a vision and a future together, rather than the continuation of having to go to court, ending up in significant conflict and creating massive uncertainty.”

The minister summed up the NDP’s environmental record to date as “much done, more to do.”

“The conservation efforts that we’re making, we are seeing the early results of those and they’re positives, but they take time, and there’s so much more we can do,” he said.