Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

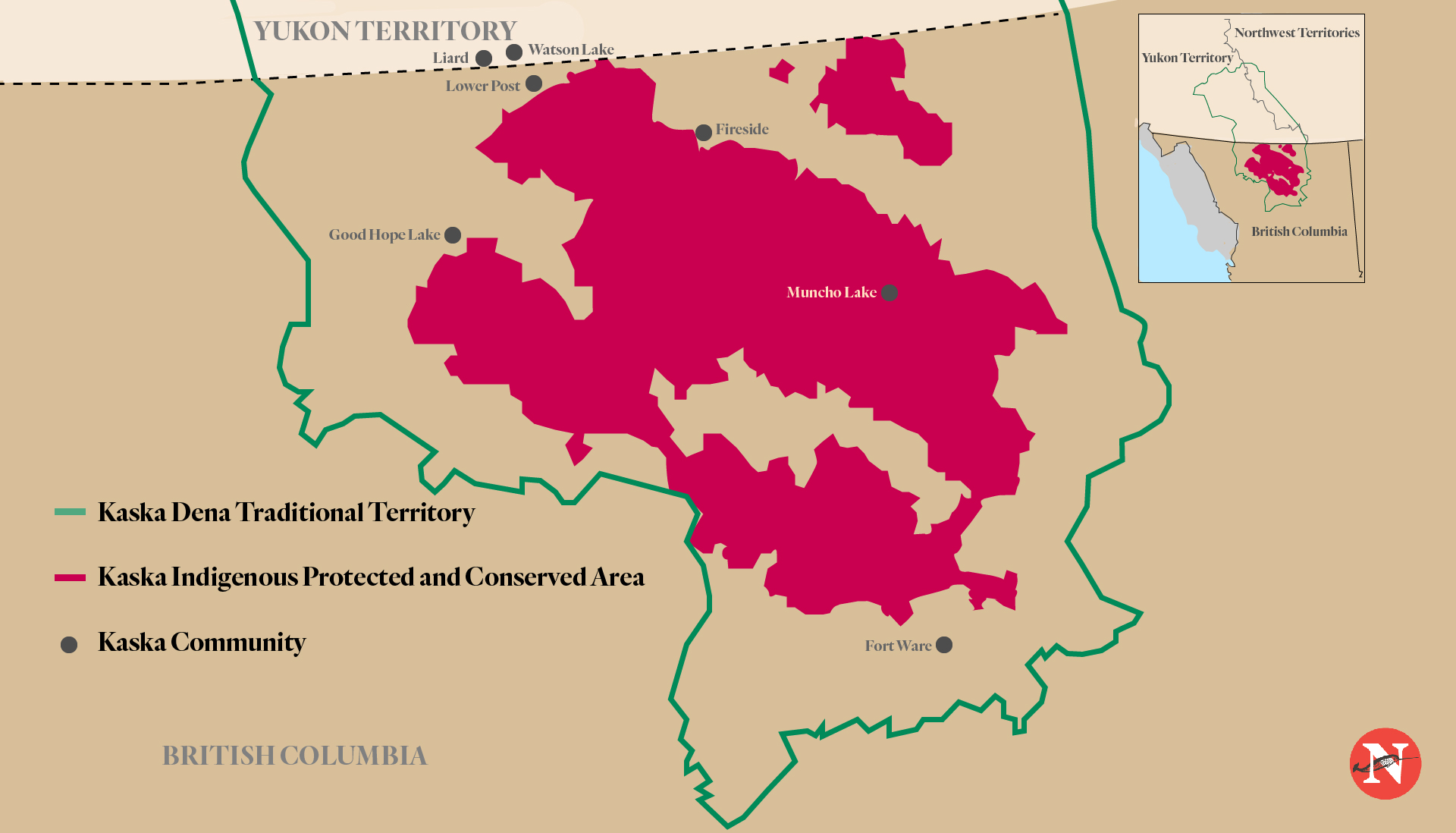

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

When old-growth forests are logged, they cannot be replicated with tree replanting. “Old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources,” Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

The remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed is as grand and as beautiful in other treasured Vancouver Island forests like Avatar grove and the Walbran valley, Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

When old-growth forests are logged, they cannot be replicated with tree replanting. “Old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources,” Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

Before and after images of Watt standing beside a large twinned old-growth cedar that he later photographed as a stump in a clearcut. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province has failed to protect B.C.’s last remaining old-growth, the pace and scale of logging has become better understood as a key driver of flooding, habitat loss and species extinction.

In response to growing public concern, the province launched a panel to perform a strategic review of old-growth forestry. The resulting report, released in September, called for massive overhaul of how B.C. manages its remaining ancient forests.

The review panel made 14 recommendations to the government, including short-term deferrals in areas with trees greater than 500 years old near the coast and greater than 300 years old inland. So far, essentially none of the panel’s recommendations have been put into action by the government.

The report noted old forests carry an intrinsic value for all living things and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber. It also emphasized that unique ancient forests are irreplaceable, even if trees are replanted.

Watt echoed the sentiment: “When you log an old-growth forest, it’s not coming back. Trees may come back … but old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources.”

Watt said the forest in the Caycuse watershed is exactly the type of forest the panel recommended protecting through immediate deferrals.

Unfortunately that recommendation is “too little too late for this forest,” Watt said.

The remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed is as grand and as beautiful in other treasured Vancouver Island forests like Avatar grove and the Walbran valley, Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

When old-growth forests are logged, they cannot be replicated with tree replanting. “Old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources,” Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

Photographer TJ Watt has seen more than his fair share of clearcuts through his work for the Ancient Forest Alliance.

Still, the sudden transformation of an old-growth forest in the Caycuse watershed on Vancouver Island into a “bleak grey landscape” caught Watt off guard.

His before and after photos, published on Instagram and featured in The Guardian, also struck a nerve with the public.

“I think it’s just with the before and after it’s very plain and simple: you can clearly see what was there and what was lost,” Watt told The Narwhal.

“These photos are going around the world now,” he said, adding he’d just sent a gallery off to a newspaper in France.

In an Instagram post that has received more than 8,900 likes, Watt noted the photos are a series he hoped to never complete. The Ancient Forest Alliance has campaigned for months, asking the province to introduce immediate and long-term measures to protect the last remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed around Haddon Creek, south of Lake Cowichan.

Watt said the Caycuse watershed was heavily logged in the 80s and 90s, “save for a few last groves on these slopes in the upper regions of the valley, where there they’ve kind of stood, alone, for the past 10 years or so.”

Now that those groves have been logged by company Teal-Jones and he has completed the photo series, Watt said he hopes the images will serve as a stark reminder of what is at stake when endangered old-growth forests are left without protection.

“This is essentially what we stand to lose, every time there is more talk and log and delays from the government,” Watt said.

Before and after images of Watt standing beside a large twinned old-growth cedar that he later photographed as a stump in a clearcut. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province has failed to protect B.C.’s last remaining old-growth, the pace and scale of logging has become better understood as a key driver of flooding, habitat loss and species extinction.

In response to growing public concern, the province launched a panel to perform a strategic review of old-growth forestry. The resulting report, released in September, called for massive overhaul of how B.C. manages its remaining ancient forests.

The review panel made 14 recommendations to the government, including short-term deferrals in areas with trees greater than 500 years old near the coast and greater than 300 years old inland. So far, essentially none of the panel’s recommendations have been put into action by the government.

The report noted old forests carry an intrinsic value for all living things and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber. It also emphasized that unique ancient forests are irreplaceable, even if trees are replanted.

Watt echoed the sentiment: “When you log an old-growth forest, it’s not coming back. Trees may come back … but old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources.”

Watt said the forest in the Caycuse watershed is exactly the type of forest the panel recommended protecting through immediate deferrals.

Unfortunately that recommendation is “too little too late for this forest,” Watt said.

The remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed is as grand and as beautiful in other treasured Vancouver Island forests like Avatar grove and the Walbran valley, Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

When old-growth forests are logged, they cannot be replicated with tree replanting. “Old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources,” Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

The Narwhal

December 10th, 2020

Between April and November, a grove of ancient trees was felled in the Caycuse watershed on Ditidaht Territory, pointing to the breakneck pace of clearcut logging across the province

Photographer TJ Watt has seen more than his fair share of clearcuts through his work for the Ancient Forest Alliance.

Still, the sudden transformation of an old-growth forest in the Caycuse watershed on Vancouver Island into a “bleak grey landscape” caught Watt off guard.

His before and after photos, published on Instagram and featured in The Guardian, also struck a nerve with the public.

“I think it’s just with the before and after it’s very plain and simple: you can clearly see what was there and what was lost,” Watt told The Narwhal.

“These photos are going around the world now,” he said, adding he’d just sent a gallery off to a newspaper in France.

In an Instagram post that has received more than 8,900 likes, Watt noted the photos are a series he hoped to never complete. The Ancient Forest Alliance has campaigned for months, asking the province to introduce immediate and long-term measures to protect the last remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed around Haddon Creek, south of Lake Cowichan.

Watt said the Caycuse watershed was heavily logged in the 80s and 90s, “save for a few last groves on these slopes in the upper regions of the valley, where there they’ve kind of stood, alone, for the past 10 years or so.”

Now that those groves have been logged by company Teal-Jones and he has completed the photo series, Watt said he hopes the images will serve as a stark reminder of what is at stake when endangered old-growth forests are left without protection.

“This is essentially what we stand to lose, every time there is more talk and log and delays from the government,” Watt said.

Before and after images of Watt standing beside a large twinned old-growth cedar that he later photographed as a stump in a clearcut. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province has failed to protect B.C.’s last remaining old-growth, the pace and scale of logging has become better understood as a key driver of flooding, habitat loss and species extinction.

In response to growing public concern, the province launched a panel to perform a strategic review of old-growth forestry. The resulting report, released in September, called for massive overhaul of how B.C. manages its remaining ancient forests.

The review panel made 14 recommendations to the government, including short-term deferrals in areas with trees greater than 500 years old near the coast and greater than 300 years old inland. So far, essentially none of the panel’s recommendations have been put into action by the government.

The report noted old forests carry an intrinsic value for all living things and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber. It also emphasized that unique ancient forests are irreplaceable, even if trees are replanted.

Watt echoed the sentiment: “When you log an old-growth forest, it’s not coming back. Trees may come back … but old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources.”

Watt said the forest in the Caycuse watershed is exactly the type of forest the panel recommended protecting through immediate deferrals.

Unfortunately that recommendation is “too little too late for this forest,” Watt said.

The remaining old-growth in the Caycuse watershed is as grand and as beautiful in other treasured Vancouver Island forests like Avatar grove and the Walbran valley, Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

When old-growth forests are logged, they cannot be replicated with tree replanting. “Old-growth forests are essentially non-renewable resources,” Watt said. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt estimates some of the trees recently cut down in the Caycuse watershed are between 800 and 1,000 years old. Photo: TJ Watt

While the province committed to temporarily defer logging in nine forests containing old-growth, critics were quick to point out little to no harvesting was expected to take place in those areas recommended by the panel. They also noted some of the deferral zones contained forests already protected in parks or forests that had already been logged.

These deferrals did not offer any protection to some of B.C.’s most quickly disappearing old-growth located in the northern boreal forest, a rare and endangered interior temperate rainforest and on Vancouver Island.

Watt stands at the remains of a large, old-growth cedar in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

The province also claims 23 per cent of B.C. forest — about 13 million hectares — qualifies as old-growth.

But a study published in June found just three per cent of B.C. is capable of supporting large trees and within that small portion of the province, the report’s authors found only 2.7 per cent of the trees are actually old. The authors note, “old forests on these sites have dwindled considerably due to intense harvest.”

“We’ve basically logged it all,” Rachel Holt, one of the authors of the study, B.C.’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity, told The Narwhal in June.

Watt said he’s disappointed the province continues to talk up its old-growth strategy, while failing to do more to protect forests like the one in the Caycuse watershed.

“When you see a tree that is 800 or 1,000 years old, reduced to this graveyard of stumps, you realize that every day, every week, every month that there is further delay in action on these endangered ecosystems, the losses we face are huge and are permanent.”

Before and after images show the extent of clearcut logging on the slopes of the valley. Photo: TJ Watt

Forestry machinery on a logging road leading to a new clear cut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt said industrial logging in B.C. often happens out of sight and out of mind of Canadians and yet the stakes are so urgent when you realize how little old-growth forest remains.

“That’s what I’m trying to get across. I’m trying to bring these remote places into people’s living rooms, onto their phones, so people can see what is happening, speak up, contact their elected officials, their MLAs, to demand an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests.”

Communities dependent on logging deserve a sustainable transition plan, so they’re not left hanging when protections are put into place, Watt said.

Increasingly, conservation groups and First Nations are asking the provincial and federal governments to create financial incentives to protect, rather than harvest, forests.

Forests that are highly productive in terms of timber yield are often forests that contain the greatest biodiversity, species habitat and store the most carbon.

The province needs to turn its attention to transitioning forest management from old-growth logging to sustainable and value-added forestry practices, Watt said.

“It’s critical the government put forward funding to support Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and support for communities that are looking to transition away from old-growth logging,” he said.

“The world is watching B.C. right now,” Watt added. “Unfortunately it took these images to capture people’s attention. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Watt said he is going to continue traveling to remaining ancient forests that can still be protected. He hopes he won’t have to publish more before and after photos.

“I’m going to keep going out there. Otherwise this would still be happening. No one would know. No one would care.”

Watt said he wants to see the B.C. government commit funding to the transition to sustainable forestry. Photo: TJ Watt

Watt walks down a Teal-Jones logging road. Photo: TJ Watt

Read the original article

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/D813709B-EB6A-4F41-9BC2-B35F51FDE885_1_201_a-80f72f11d4d941dca85d43875adaf50c.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/D81CB965-F171-44C5-B6D6-D3302E95B553_1_201_a-a9292e4b933149b5a2c49f24630367e6.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/3E4FAA31-A76C-4FDF-969B-1B5D5A6D828A_1_201_a-cc58a003a44a463397d12d405f72908e.jpeg)