Falling fast

Three decades after the so-called ‘War of the Woods,’ the logging of B.C.’s ancient forests goes on, prompting protest from a new generation of eco-activists

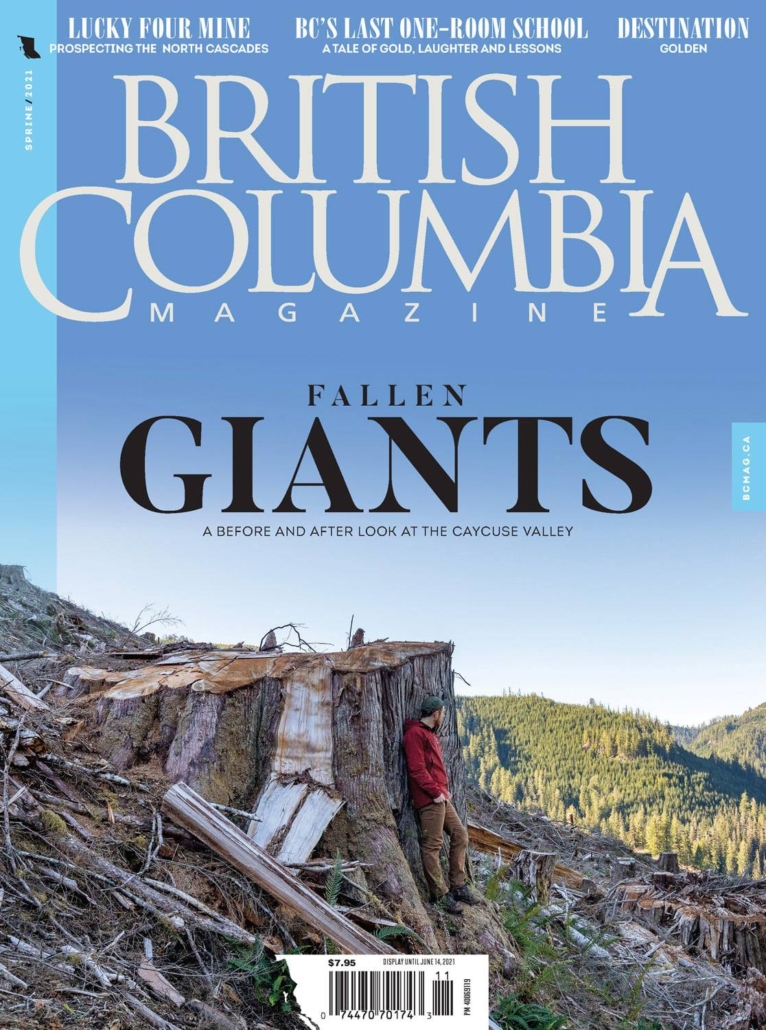

Watt’s ‘before and after’ photos have drawn worldwide attention to old-growth logging in B.C. (TJ Watt)

McLean’s magazine

April 13, 2021

It came as a bit of a shock to Shawna Knight, a 43-year-old mother of two who runs the Buddha Box, a locally sourced food outfit in Shirley, on Vancouver Island’s southwest coast. Co-founder of the famous Cold Shoulder Cafe in the local surfing mecca of Jordan River, Knight says she figured she was as clued in as anyone to what was happening in the wild world around her. “We hunt for mushrooms, we do nettles every spring. I felt like we were connected. But we weren’t. We so obviously were not.”

Knight says she’d taken it for granted that the days when British Columbia was internationally notorious for cutting down the world’s last remaining stands of temperate old-growth rainforest were well and truly over. She thought the “War in the Woods” that had brought thousands of protesters to Canada’s West Coast from all over the world, when she was in her teens, had been fought and won. “Boy, was I wrong,” Knight tells me. “I just assumed we weren’t old-growth logging anymore. Turns out we’re doing it as fast as we can, right now.”

The realization came like a bolt out of the blue following a chance find on a Facebook chat group last summer—the ancient trees were still falling. It’s what prompted Knight to shut down the Buddha Box and spend her time ever since, a week on and a week off, where I met her: at a blockade on a remote logging road known as the Edinburgh Main, a branch of the Gordon River Main, in the mountains above Port Renfrew, an old fishing and logging town about two hours’ drive northwest of Victoria.

The camp on the Edinburgh Main is one of a half-dozen protest sites that have been springing up and moving around since last August on roads that the Teal-Jones logging company has been trying to punch into the Fairy Creek watershed, one of the last unprotected old-growth valleys on Vancouver Island.

The Teal-Jones Group is a 70-year-old logging and milling firm that bought the provincial timber rights to a huge tract of Vancouver Island’s southwest forests—Tree Farm Licence 46—in 2004. Ever since the first blockade appeared last August, the company has been in and out of court, hoping for an injunction that would order the dozens of protesters who have been encamped on its roads to get out of the way.

Although no cutblocks had been authorized within the Fairy Creek watershed, Teal-Jones says it is within its rights to log there, and it intends to take trees from only about 200 hectares of the 1,200-hectare watershed. The company is just trying to build logging roads to get at the trees. It sounds like a fairly straightforward contest. But it isn’t.

It’s not just about the Fairy Creek watershed, and it’s not just about TFL 46. In some ways, it’s as though the War in the Woods that began in the mid-1980s and lasted a decade is still going on. “It never really ended,” Knight tells me.

***

But there’s a lot that’s different about “protest” this time around: digital technologies, the rise of social media, the new capacities available to First Nations authorities, the economic transformation of formerly logging-dependent communities, and the realigned roles of the federal and provincial governments.

It’s not even clear how it came to pass, exactly, that all those protesters suddenly showed up last summer camping in cars, tents and old buses in the mountains around Fairy Creek. But it would appear that word of a Teal-Jones logging road breaching a ridge line above the watershed first came from Joshua Wright, a 17-year-old activist and filmmaker with highly developed computer skills. Wright had been live-monitoring road construction in the area using advanced digital-mapping software from his home across the Juan de Fuca Strait and across the Canada-U.S. border in Olympia, Wash.

Knight in a camp bus at a blockade (Photograph by Jen Osborne)

That’s a far cry from what might be called the first shot fired in the War in the Woods back in the 1980s. You could situate that event on Nov. 21, 1984, when Tla-o-qui-aht Chief Moses Martin stood on the beach of Meares Island, just off Tofino in Clayoquot Sound, and addressed a group of MacMillan Bloedel officials and loggers who’d arrived to start clearing the forest. Martin told them their provincially issued logging rights counted for nothing against Tla-o-qui-aht law, and that they were welcome to stay for a meal but they’d have to put down their chainsaws first.

The MacMillan Bloedel party withdrew, but not without a fight in the courts. They lost, and so did the provincial government. Sixteen years later, Clayoquot Sound, with its giant trees still standing after 1,000 years, towering as high as 20-storey buildings, was a UNESCO biosphere reserve. Along the way, thousands of protesters had made their way to Vancouver Island to protest old-growth logging. In one protest, at the Kennedy Lake Bridge, 859 people were arrested and eventually convicted on contempt charges for violating an anti-blockade injunction. It’s still considered the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

The activists and the Tla-o-qui-aht won most of their demands, and further prohibitions on industrial-scale logging were secured in the nearby Megin River Valley, portions of the Walbran and Carmanah valleys and other remnants of ancient forest on Vancouver Island immediately north of Teal-Jones’ TFL 46. On B.C.’s mainland coast, where much of the readily accessible timber had already been taken out, the Great Bear Rainforest was made off limits to further large-scale logging.

Over the years, there were other compromises between the lumber and conservation interests as the industry went through a series of convulsions, including a pine beetle infestation that carried off much of B.C.’s Interior woodlands. Then came years of forest-protection backsliding during the Liberal party governments of Gordon Campbell and Christy Clark.

When New Democrat John Horgan was elected with a Green-backed minority in 2017, hopes were high that Vancouver Island’s dwindling ancient forests would win some reprieve—TFL 46 falls entirely within Horgan’s home riding of Langford-Juan de Fuca. There was much consultation and study, including a key “Old Growth Strategic Review.” When Horgan beat back the Greens and the Liberals to form a majority in last September’s snap election, he had his eye on the public’s hardening mood: a 2019 opinion poll showed 92 per cent of voters wanted action to protect endangered old-growth forests, partnerships with Indigenous people and a more diversified economy.

Logging truck drivers protesting forest-industry layoffs in 2019 (Darryl Dyck/CP)

Teal-Jones, too, insists the company intends to meet the high standards the public increasingly demands. In a recent statement, Gerrie Kotze, the company’s chief financial officer, declared: “Our work on this tree farm licence will be done in a way consistent with our values of sustainable forest management.” Teal-Jones, he added, “is committed to harvesting with the care and attention to the environment.”

Conservationists heralded the Old Growth report and its recommendations as the makings of a welcome “paradigm shift” in B.C.’s dysfunctional forest policies, putting ecosystem health above all other considerations. While Horgan’s government committed to following the review panel’s recommendations, further consultations would be required. Horgan nonetheless pledged to protect “nearly 353,000 hectares of old-growth forests,” in nine large areas, saying, “that’s just the beginning.”

Then the caveats began to reveal themselves. The nine parcels weren’t being “protected,” exactly. Logging was merely being deferred for two years. As for the “old-growth” in the deferral areas, half the landscapes were either alpine bonsai trees, or not even forest, or second-growth, or old-growth that was already protected. The Ministry of Forests had to clarify that only 196,000 hectares of “old-growth” was involved. In any case, when would the “paradigm shift” laid out in the review actually begin?

Maclean’s reached out to newly appointed B.C. Forests Minister Katrine Conroy’s office for answers. Will the review’s recommendations be implemented within the deferral’s two-year timeline? Conroy’s spokesperson, Tyler Hooper, explained by email that it’s going to take time because the government is committed to “doing this right,” adding that the Old Growth panel’s timeline “related to when work should be under way,” not completed. Besides, he noted, the recommendations came before the COVID-19 crisis: “We’ve started high-priority work in keeping with the report’s recommendations. But it will take engagement with the full involvement of Indigenous leaders, organizations, industry and environmental groups to find consensus on the future of old-growth forests in B.C.”

A closer review undertaken by forest ecologists Karen Price and Rachel Holt with professional forester Dave Daust, authors of the report “B.C.’s Old-Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity,” reckon that only 3,800 hectares of Horgan’s deferred 350,000 hectares contain forests of the type that the Old Growth panel classified as in need of immediate action. So about one per cent, in other words, was forest of the ancient, tall-tree kind that most people imagine when they hear the term “old-growth.”

***

You have to squint at all these numbers to notice the point that the activists are trying to make when they say the bad old days in British Columbia are back. It’s complicated, and that’s where Ancient Forest Alliance photographer TJ Watt comes into the picture. He’s one of the main reasons that a handful of activists who first met at Lizard Lake near the Teal-Jones Granite Main logging road last August have acquired so many friends and well-wishers.

The 36-year-old Watt has been cutting through the cacophony of data with photographs. After a childhood in rural Metchosin, just outside Victoria, and summers in Port Renfrew, where his parents ran a marina, Watt has emerged as a key figure in the campaign to save the few groves of ancient forest that remain on Vancouver Island’s southwest coast. He’d found himself enchanted by the forest early on, and by his early 20s he’d developed a fascination with photography.

Watt’s leadership in the Ancient Forest Alliance grew out of a random event, in his early 20s, when he came upon the Western Canada Wilderness Committee’s storefront office on Johnson Street in Victoria. He walked in and hit it off right away with WCWC’s veteran campaigner, Ken Wu, who put him to work taking photographs of a forestry protest rally in town. Ten years ago, after Watt and Wu struck out on their own and founded the Ancient Forest Alliance, Watt found himself drawn deeper into Vancouver Island’s distant groves of cedar, fir, hemlock and spruce.

“The more remote landscapes were a blank spot on the map to me,” Watt says. “You spend three or four hours on a logging road, and then you arrive in this wonderland, with cascading waterfalls and emerald green pools and rivers, and these ancient forests, with trees that are nearly five metres across. I was just blown away how these forests were not protected.”

Watt’s early photographs of the still-standing trees in the unprotected portions of the Walbran Valley, and his 2018 portraits of the just-felled giants in the entirely unprotected Nahmint Valley near Port Alberni, caused a sensation. The photographs were partly a catalyst for the Horgan government’s old-growth review.

But it was last November that his disturbing “before and after” pictures of Teal-Jones logging operations in the Caycuse Valley drew international attention. “That was an explosion,” he says. “People from around the world get it, when they see the striking contrast in a tree that’s lived for 800 or 1,000 years, and the next day, it’s gone.”

His methodology is straightforward. He finds a big tree, picks an angle, sets up his tripod, shoots his photographs, and keeps careful notes—measuring the distance from the camera to the tree with a range finder; taking reference photographs of his set-up; noting the camera lens he’s used; noting the focal length; and recording the GPS coordinates so he can accurately retrace his steps through the logging slash to the “before” location, to take an “after” photograph.

Watt posted his first Caycuse “before and after” photographs on his Instagram account on Nov. 24, and they’ve since shown up in the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper, Outside magazine and countless social media posts. The scenes he depicted have been seen by millions of people.

“Humans are visual creatures, and photography allows you to understand an issue in an instant,” Watt says. “People see that it’s a permanent loss. Old-growth forests do not come back. We get one chance, and one chance only, to save these trees.”

Wu in the Avatar Grove forest (Photograph by Jen Osborne)

Because of the mischief they’ve been making in and around TFL 46, you’d think TJ Watt, Ken Wu and the Ancient Forest Alliance would be considered villains in a town like Port Renfrew. They’re not. They’re more likely to be considered heroes.

In the forests above the town, Wu and Watt have drawn widespread public attention to several patches of old-growth—like Avatar Grove and Eden Grove—and to individual trees with names like Big Lonely Doug, the San Juan Spruce and the Red Creek Fir. Avatar Grove, named after James Cameron’s blockbuster 2009 science fiction movie, is now classified as a forest ministry recreation site, and it’s become world-famous. Every year, tens of thousands of people visit the strange and mossy stand of giants, while Port Renfrew has taken to billing itself as the “Tall Tree Capital of Canada.” What the forest industry took away, the tourist industry is giving back.

That’s another huge difference from the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, the whole point of forest policy on Vancouver Island’s west coast was to convert old-growth forests, with their wolves, Roosevelt elk, black-tailed deer, black bears and cougars, into monocultural tree plantations. In those pseudo-forests, as the celebrated B.C. environmentalist Vicky Husband used to put it, “a deer would have to pack a lunch.”

***

The Teal-Jones Group isn’t simply the villain of the piece, either. The company is one of the loudest industry voices behind a broad-based move spearheaded by environmentalists to push back on the pace and scale of raw log exports from B.C.’s coastal forests.

Dozens of sawmills have closed over the past 20 years, and B.C. forests ministry records show that from 1998 onward raw log exports to China, the United States and elsewhere grew from about one per cent of the coastal cut to 30 per cent by 2018, reaching a recent average of four million cubic metres annually.

To put that in perspective: because a standard logging truck can hold around 40 cubic metres of timber, the volume of unprocessed logs from coastal forests shipped out of B.C. has been adding up to the equivalent of 100,000 fully loaded logging trucks in a bumper-to-bumper convoy stretching roughly from Vancouver to Winnipeg, every year.

Another big change from the days of the War in the Woods: First Nations are increasingly becoming major players in the forest industry.

Watt’s photos of old-growth logging (like his drone image of Caycuse, above) exploded on social media (TJ Watt)

The Fairy Creek watershed, along with almost all of TFL 46, falls within the traditional territory of the Pacheedaht Nation, a community of about 300 Nuu-chah-nulth people. While the Pacheedaht forestry initiatives include a set-aside for 400 years’ worth of cedar sufficient for their traditional ocean-going canoes, the Nation now also manages or co-manages an annual cut of about 140,000 cubic metres and runs its own small sawmill. It takes a percentage of the stumpage fees from every tree cut down in its traditional territory and co-owns a portion of Tree Farm Licence 25 in the Jordan River watershed. The Pacheedaht have declined to take an official position in the Fairy Creek controversy.

Ken Wu, the veteran forest activist, has since moved on to establish the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, which works mainly at the federal level. Wu, who now works out of Montreal, tells me a major change from the 1980s and 1990s is that, while logging-road blockades are a necessary “catalyst” to action, the harder and more lasting work involves building broader alliances with “non-traditional” partners in the resource industries.

The Trudeau government has committed Canada to achieve 30 per cent protection of marine and terrestrial ecosystems by 2030. Wu says that’s not near enough. The Endangered Ecosystems Alliance is aiming for 50 per cent. As for holding the line to protect the last stands of Canada’s West Coast temperate rainforest, Wu says the key is offering Indigenous communities a viable alternative to the trap between a rock and hard place—between old-growth logging and poverty.

“The point is, there’s hardly any of the high-productivity old-growth left,” Wu says, “and we have to protect everything that remains. B.C. is one of the very last jurisdictions on earth that still condones and supports the large-scale logging of 500- and 1,000-year-old trees. It doesn’t grow back. Once it’s gone, it’s gone forever.”

This article appears in print in the May 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Falling fast.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

Read the original article

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/RXDP4RDGUFAYTN7CU6ZJ3UXFZA.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/SLFSCJSWAJHJ3CZJPCXSITYLXI.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/M3YP7QHQVBA7FHOWQMED77TL7Q.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LHEEMPWBNJG3VCVS4OEMMGQJ7M.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LHZSIU7JPZEIJFOGJJNKEQOTYY.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DGKLLWANP5CW7CRTK6P534N7ZM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/IWMLSARQAJB6HDKEBUQOX4EQUQ.JPG)