Chek News

March 20, 2021

B.C.’s New Democrat government, once an ally of environmentalists in protecting the province’s ancient forests, is now facing increasingly heavy criticism for its failure to stop the logging of the province’s remaining old growth trees.

Premier John Horgan has recently seen his constituency office targeted for protest by those opposed to old growth logging, a forest company in his riding blockaded by activists and his forests minister grilled by the opposition B.C. Greens in the legislature. On Friday, as many as 300 environmental supporters marched through downtown Victoria to demand government halt old growth logging.

At issue is whether the government is following recommendations in an expert panel report it commissioned, one of which calls for a halt to old growth logging, in areas where ecosystems are at high risk of irreversible biodiversity loss. That pause was supposed to be in place by this month, according to the report’s timeline, to give the province time to craft an old growth plan.

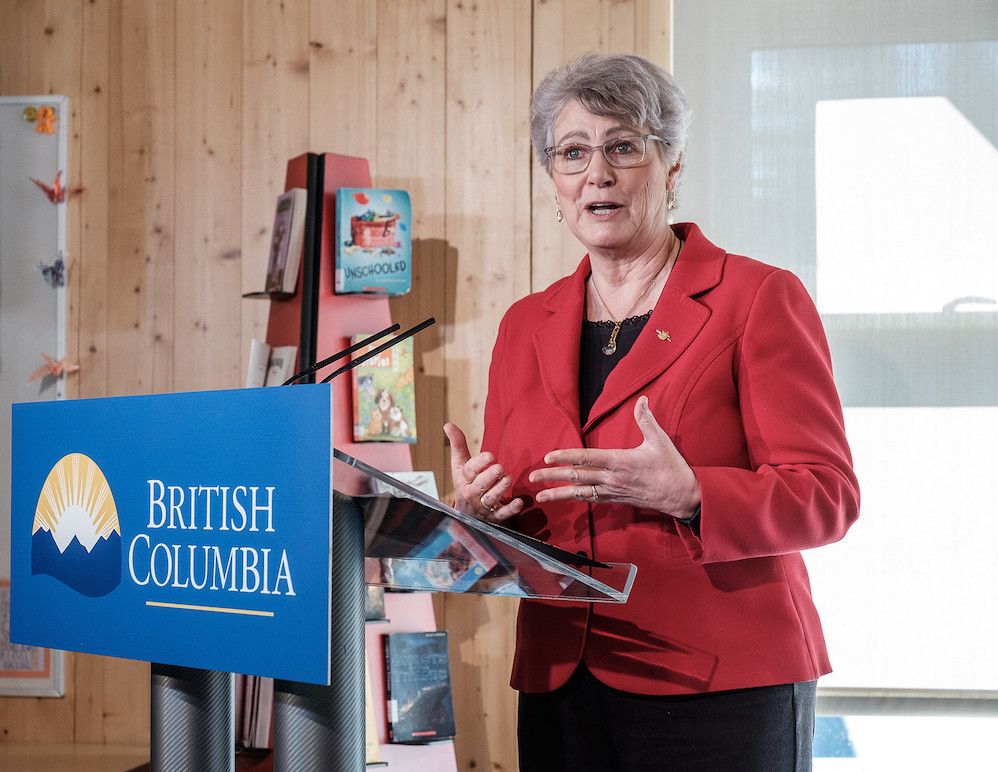

Forests minister Katrine Conroy insists government has taken “a first step” by in September deferring logging in 353,000 hectares at nine locations, including Clayoquot Sound and McKelvie Creek on western Vancouver Island, as well as H’Kusam near Campbell River.

“It’s complicated,” Conroy said in an interview. “It’s not just as easy as to say, oh yes we’ll have a moratorium on all old growth in the province, which is actually something the report did not recommend. They recognized there is going to be some old growth logging in the province.”

However, only a small fraction of the old growth Conroy deferred from logging is actually high-productivity and at risk of logging — and in some cases the province is double-counting forests it has already preserved. It also isn’t actually banning logging in those protected areas, instead allowing companies to harvest second growth in and amongst the ancient trees. The reprieve comes with a two-year expiration date.

Environmental groups and the Greens accuse the NDP of dragging its feet on the file, out of fear of harming blue-collar forestry jobs in unions like the United Steelworkers, which continue to be power-brokers within the New Democratic party.

“Here’s the problem with how they’ve approached it, they come out and make announcements like, ‘Oh look at the good work we’ve done,’ and then you go pick it apart and realize it’s not an honest statement at all,” said Green leader Sonia Furstenau.

The province’s expert report. which was completed and released during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, recommended detailed consultation with First Nations, a new forestry framework, bringing forestry management into compliance with targets to maintain biological diversity for old growth, as well as more robust mapping, policy, and old growth classifications. Overall, B.C. should enact legislation that declares the conservation of ecosystem health and biodiversity as its overarching goal, the strategic review recommends.

Little, if any, of that has actually happened, say critics. Instead, they accuse the government of leading with rhetoric and platitudes from the premier and his ministers.

“I’m afraid we’re not going anywhere,” said Furstenau. “By the time anything actually starts to happen in earnest, the forest that will be lost by then, you can’t replace them, and that will be the legacy of this government. It will be a legacy of destruction of ecosystems that were astonishingly rare.”

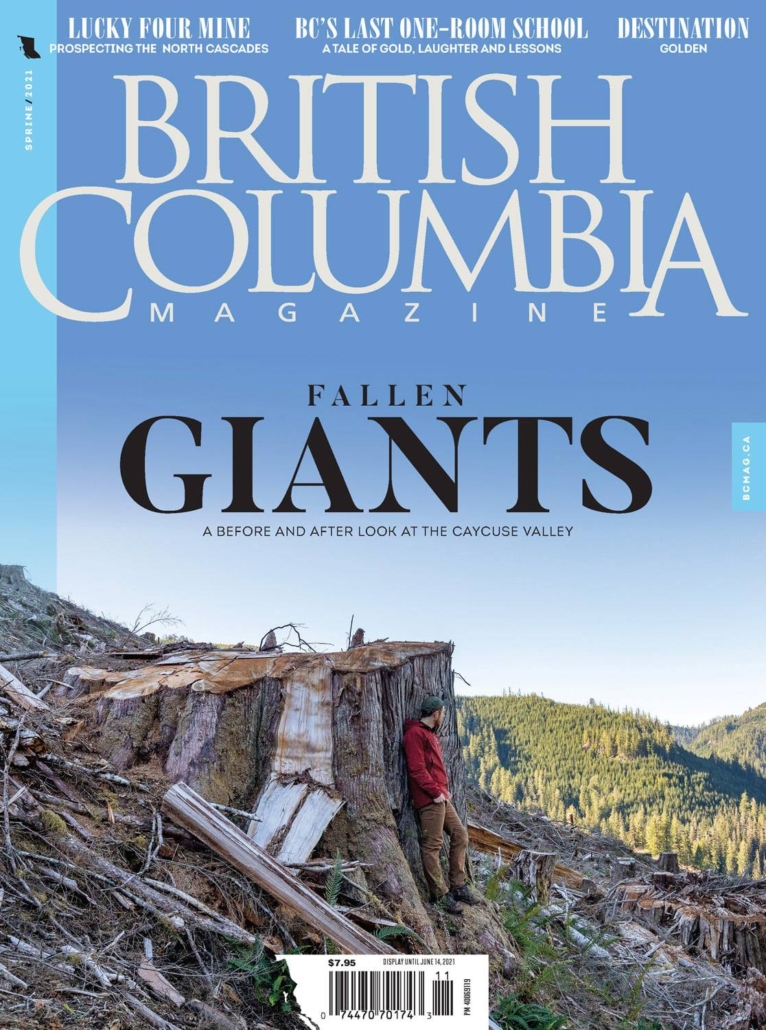

‘Hardly’ any old growth left, say activists

B.C. has roughly 50 million hectares of forest, of which 13.7 million is considered old growth — trees more than 250 years old on the coast and 140 years old in the interior. But not all old growth fits the commonly-associated picture of gigantic and soaring Douglas Fir or Western Red Cedar trees — much of it is bog, or small high-alpine trees that are old but nonetheless small enough to grab with one hand.

Only 108,000 hectares is large, old, picturesque traditional old growth forest, and that’s less than eight per cent of what was there in the past due to logging, said Rachel Holt, a longtime old growth ecologist who runs Veridian Ecological Consulting and has crunched the province’s forestry numbers.

“There’s hardly any of it left,” she said. “It is highly endangered. If it’s not protected, it’s going to be logged in the near future.”

Conroy has responded to criticism by arguing September’s deferral of 350,000 hectares of old growth will give the province the time to do the consultation required with First Nations, forestry companies, environmental groups and forestry-dependent communities about how to balance valuable old growth logging with environmental protection. There are also aboriginal communities that depend on old growth logging and partner with forestry companies to provide jobs for their community, she said.

“For some people, it will never be enough what we do, because they have that laser focus only on old growth, not on any of the other issues that come up with this,” said Conroy. “There’s thousands of people across the province who have good family supporting jobs because of the forest industry, and we have to make sure we take that into consideration.”

The old growth report recommended government begin indigenous consultation and defer logging in ecosystems at very high risk within six months, so it can work on other goals that could take as a long as three years. That six months was up in March. Conroy argues both recommendations are underway, but environmental groups say the NDP is just stalling for time.

“The NDP are banking on a strategy which is that there’s a whole lot more rural working class votes than urban idealist tree hugging super leftist types in Victoria so we’re not going to be catering to that protest crowd,” said Ken Wu, who has spent 30 years campaigning to save old growth forests and is now executive director of the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance.

“But the reality is if you look at public opinion poling the vast majority of people, pervading different classes and areas, is we need to save old growth and log second growth.

“The NDP have read it wrong. They are classic old-school industrial union labour guys.”

Furstenau, Holt and environmentalists like Wu point to Conroy’s claim 350,000 hectares of old growth has been deferred for protection as an example of the NDP playing with numbers to distract the public from its inaction.

Of the 350,000 hectares Conroy deferred in September, 100,000 hectares is not forested at all, and a further 100,000 hectares doesn’t contain old trees, calculated Holt. The remaining approximately 150,000 hectares of old growth contains actually 5,637 hectares of productive old growth, and 1,849 hectares of that was already protected, she said. That means less than one per cent of what the minister announced as protected is actually what the public would consider traditional large old growth forests, she said.

The goal is to give the perception of progress where little exists, said Wu.

“They are like, let’s let Ken Wu sputter about productivity distinctions in complex phrases while we trot out our simple sounding catchy statistics and words, and then let the confusion set in to buy time to talk and log,” he said. “But I think people are getting more and more aware.”

The flashpoint of the entire dispute is Fairy Creek, an ancient temperate rainforest and valley near Port Renfrew. A group of protesters have blockaded access to the area for almost eight months in a bid to prevent forest company Teal Jones from logging in the area.

“This is the last stand for old growth forests,” said Joshua Wright, a spokesperson for Rainforest Flying Squad, the environmental group running the blockades.

Teal Jones is in B.C. Supreme Court this week seeking an injunction that, if enforced, could see the protesters arrested.

Wright said he expects a similar scene as in 1993, when almost 1,000 people were arrested for protesting logging Clayoquot Sound, in what became known as the War in the Woods. That incident also occurred during the last NDP government in B.C.

“There was the war in the woods in the 1990s — that was 30 years ago, but it’s still going,” said Wright. “If we don’t stop it now … they will all be gone in a matter of years. What we’re planning on doing is taking a last stand for these forests.”

Conroy said the province has to take the time necessary to craft policies that balance logging and forest protection, or else the system won’t be sustainable for the future. Forestry companies need to partner with local First Nations and pursue diverse long-term goals as well, she said.

“My goal is to have a sustainable forest industry,” she said. “I look at my grandkids, if they want to work in the forest industry I want to make sure if when they are old enough they can. And if they want to go for hikes in the woods and see old growth forests and see those forests, that they have that opportunity too.”

Furstenau said the province simply needs to have the courage to follow the expert report’s call for a paradigm shift in how it protects old growth forests. Anything short of that is a betrayal of what Horgan has previously promised, she said.

“It is disappointing but not out of character,” said Furstenau. “This is what we’ve seen from successive governments from this province, and now we’re at the point where we’re literally talking about the last bits of remaining old growth and whether we just let it all get chopped down or do we actually make an effort to change things.”

The B.C. government is facing criticism it has failed to protect old growth forests from logging. (Photo by TJ Watt, submitted to CHEK News)

Read the original article

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/RXDP4RDGUFAYTN7CU6ZJ3UXFZA.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/SLFSCJSWAJHJ3CZJPCXSITYLXI.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/M3YP7QHQVBA7FHOWQMED77TL7Q.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LHEEMPWBNJG3VCVS4OEMMGQJ7M.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LHZSIU7JPZEIJFOGJJNKEQOTYY.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DGKLLWANP5CW7CRTK6P534N7ZM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/IWMLSARQAJB6HDKEBUQOX4EQUQ.JPG)